Dogs Damour How Do Fall in Love Again Video

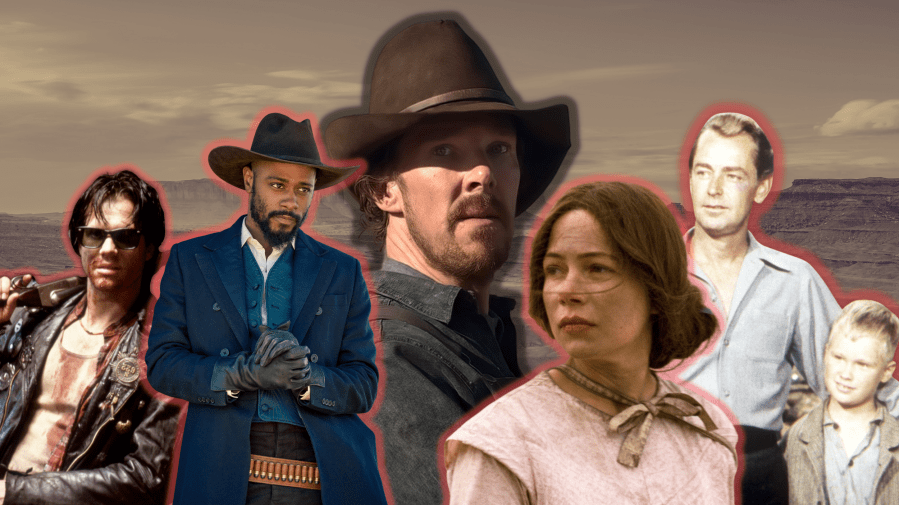

In the days leading up to the Oscars, Jane Campion'south film Ability of the Dog got me thinking well-nigh Westerns. For a moment, I was having what I idea were some actually insightful thoughts about how rare it is for a Western to win All-time Picture. Then I remembered that Nomadland, the moving-picture show that won Best Pic just last year, was described as a Western by many.

Westerns, in a mode, are pure Hollywood. The classics of the genre are concerned with wide-open spaces and the frontier, with possibility and individuality — in and so many ways, Hollywood itself, at the western limit of the continent, where the desert finally meets the sea, is the culmination of all these concerns. Near immediately though, filmmakers started making revisionist Westerns — stories that reacted confronting the commonplace tropes of the genre. Films similar Nomadland, with its desert scenery and commentary on loneliness, and Ability of the Dog, with its examination of the rot underneath masculinity, utilise the themes of the traditional Western to say something of import well-nigh where nosotros are now.

I've loved the Western for as long as I can remember — even some of the early on ones that don't seem to exist examining much of anything. I'm easily won over by the magic of the movies writ large; I'k taken in by big scenery, dramatic moods, gunfights, you name information technology. Still, I'thou likewise a person who wants to think virtually what it all means, what I might be ignoring, and what I might take missed, and then the Westerns I really love are the revisionist ones. Here are some swell ones that enquire the big questions while remaining incredibly exciting, moving, and even fun to watch.

The Ox-Bow Incident (1943)

The Ox-Bow Incident combines the setting of a Western with the drama of a courtroom, and with a running time of just 75 minutes, it'south the shortest film on this listing. The film centers around a crime: a small-scale-town cattle rancher has been killed, and the townspeople are already on edge because in that location have been recent instances of cattle-rustling. The town forms a posse, and the posse heads out and quickly finds three men in possession of the expressionless man's cattle. The movie itself follows the dilemma of how to serve the demands of justice.

I won't ruin the whole plot for you, but this is a film almost the difficulty of standing up to the mob, and the danger of jumping to conclusions. The standard Western movie thought — that there is a clear delineation between right and wrong — is turned around here; watching the picture, you can't help but feel implicated and immersed in the drama. Henry Fonda's moving performance as a human overwhelmed by the mob volition probable stick with yous for a long time.

Shane (1953)

In George Stevens' Shane, Alan Ladd plays the title grapheme, a gunfighter who appears out of nowhere in the midst of an ongoing dispute between a wealthy cattle baron named Ryker and the homesteaders who have legally claimed pieces of land Ryker considers to be his. What makes Shane then great, though, is all the stuff going on below the surface.

This movie is sort of famous for its unspoken sexual tension — the famous scene of Alan Ladd'due south Shane and Van Heflin's Joe sweatily demolishing a giant tree stump comes to mind. It'south a movie about want — everyone seems to obsessively want Shane in some way, whether it's to beloved him, to impale him, or, like trivial Joey (a scene-stealing Brandon deWilde), to just be in his presence as much as possible.

Shane himself seems to exist impossibly controlled, cautious, and good, which makes everyone around him crackle with a kind of nervous energy. Even so, Shane knows there is a darkness within him that he can't escape. The complicated, unspoken, inevitable mystery of that darkness is what makes this movie so special.

Johnny Guitar (1954)

At the center of Nicholas Ray'south Johnny Guitar is an all-time great flick star functioning past Joan Crawford equally Vienna, a strong, entrepreneurial owner of a saloon on the burgeoning railroad, which — in classic Western manner — is opposed by the local cattlemen. Vienna sees the future coming, and she wants to be in position to capitalize on it; she knows that it's a cruel world, peculiarly for a woman, and she wants to be able to have the resources to take care of herself.

Vienna'due south confidence and independence draws the ire of Emma Small, played with explosive jealousy and rage by Mercedes McCambridge in, for my money, one of the greatest villain performances e'er. The conflict betwixt these two women drives the story, and that'southward just one of the revisionist subversions going on in Johnny Guitar. Somewhat ignored in its time, information technology's since been praised by some of the greatest filmmakers from around the world — Martin Scorsese, François Truffaut and Shinji Aoyama, just to name a few — for its boldness and for the style it warps the Western genre.

The Man Who Shot Freedom Valance (1962)

This film was directed past John Ford, the legendary filmmaker whose career embodies the progression from traditional Westerns, similar 1939's Stagecoach, to revisionist Westerns, like this 1. The Homo Who Shot Liberty Valance is nigh an aging U.Southward. Senator looking dorsum on one of the most significant moments of his life — his supposed shooting of an outlaw by the name of Liberty Valance.

The story — told mostly in flashback — is structured around an ongoing argument between Jimmy Stewart'due south Bribe Stoddard, who believes in non-violence and the prominence of the law, and John Wayne's Tom Doniphon, a classic Western cliche of a man who believes that, in the end, evil can only be stopped by force. Which side ultimately wins the argument and how history remembers the events of the past are questions that will stick with you long subsequently you lot've seen this film.

The Wild Agglomeration (1969)

One fashion to revise a genre is to exaggerate it and blow information technology out of proportion. Westerns, of grade, frequently revolve effectually violence, merely that violence tin can end upwards existence glorified — the glory of the fastest gun, for example. The Wild Agglomeration, Sam Peckinpah's film nearly a grouping of aging outlaws going afterward i final score, is packed so full of violence — smashed together in rapid cuts and parallel edits — that it leaves you utterly overwhelmed. Instead of glorifying the violence, it makes the violence feel existent, devastating and terrifying.

Peckinpah pays lots of attention to the everyday people whose lives are shattered by the violence effectually them. These people, off to the side of the main action at all times, create a feeling of ambiguity nearly the deportment of the so-called heroes. In the best way possible, The Wild Agglomeration is a Western I love that can too make me question why I love Westerns.

About Dark (1987)

I wanted to brand sure to include at least one moving picture here that revises the ideas of the Western by calculation elements from outside the genre, and Almost Dark is a great example. Managing director Kathryn Bigelow (who afterward won a Best Managing director Oscar for The Hurt Locker in 2008) made this genre brew-up of Westerns and Horror Movies. It's also a kind of love story betwixt a swain named Caleb and a daughter named Mae — who also happens to be a vampire.

Nigh Night amplifies some of the questions well-nigh violence and The West that directors like Peckinpah were dealing with, simply does so past calculation supernatural elements to the equation. The result is totally unsettling, and the characters actually stick with you. Like most people in Westerns, they're trapped in the context of the setting of their lives, and this motion picture treats them with a tenderness that will surprise you given all the horror and gore happening throughout.

Meek'south Cutoff (2010)

I'm an enormous fan of the films of Kelly Reichart, who also directed 2019's First Cow, a movie that veers into revisionist Western territory as well. Meek's Cutoff is an intense, quiet movie about a group of settlers heading westward across the Oregon desert in 1845. The settlers are existence guided by Stephen Meek, played by Bruce Greenwood, but they kickoff to suspect he's lost. As the voyage stretches out, they begin running out of food and water.

Most interestingly, the movie critiques the gender norms of the twenty-four hours in a way that can't help but leave you thinking well-nigh how far we however have to go. The men in the group are in charge, and the wives are forced to look on while the men debate about how long to get on following Meek. In a way, it all feels like an elaborate joke, and yous might first to really feel the overwhelming stupidity of the situation. I won't spoil what happens, but the ending turns the situation on its head, leaving u.s.a. wondering where we go from here.

True Grit (2010)

This adaptation of the novel by Charles Portis (it was likewise fabricated into a motion-picture show in 1969 starring John Wayne and marked his only Oscar win) is the story of a young daughter who sets out to bring the man who killed her father to justice. Hailee Steinfeld was nominated for an Oscar for her incredible performance as the immature girl, Mattie Ross, who hires an aging lawman named Rooster Cogburn (Jeff Bridges) to aid her.

In both the novel and this adaptation, Mattie's perspective is at the heart of every moment, and that's what makes the motion picture and then special. Filmmakers Joel and Ethan Coen show us the earth through Mattie's optics, so what is in many ways a common Western story — a good person who was wronged sets out for justice — is given a surprising frame of reference.

Really, it's a story about a kid who finds that the adults around her don't actually know how to brand the world work the style it should. Steinfeld's Mattie is one of the well-nigh salient heroes on this list, and the film's ending, with Mattie looking back on the greatest run a risk of her life, is i of the most moving I can think.

The Harder They Fall (2021)

I'll end this list with this recent film by Jeymes Samuel, a classic Western revenge story about a man who learns that the human being who killed his parents is about to be released from prison. Every member of the principal bandage of the movie is Blackness, and that context is part of the signal of the picture show. All of these characters — good and bad — are trying to carve out a place for themselves in the W. In one of the nearly salient images of the movie, when the primary characters rob a "white town" later in the film, everything in the boondocks is literally vivid white.

Nether his stage name, The Bullitts, Samuel did the unabridged score for the film, and the music does the aforementioned thing the visual style of the movie does: mashes upwardly genres and eras to create a new commentary on the Western. Elements of hip-hop, R&B, and reggae serve to make the film feel authentic within itself. It looks and feels like the Old West, but it also looks and feels make new. At that place'due south something exhilarating at seeing the incredible cast of this flick — again, all Black — in the midst of a genre that historically excluded Blackness people. Hollywood has been making Westerns for over 100 years now, and it'south nice to know that they can still feel like something I've never seen before.

Source: https://www.ask.com/entertainment/revisionist-westerns-if-you-loved-power-of-the-dog?utm_content=params%3Ao%3D740004%26ad%3DdirN%26qo%3DserpIndex

0 Response to "Dogs Damour How Do Fall in Love Again Video"

Post a Comment